Como funciona?

1

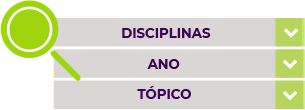

Pesquise diretamente pela barra de busca abaixo ou filtre as questões escolhendo segmento, disciplina, assunto, tipo de avaliação, ano e/ou competência.

2

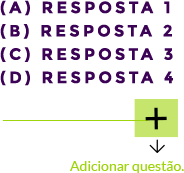

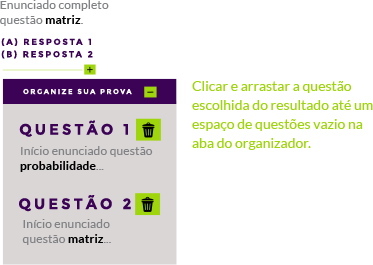

Clique no botão [+] abaixo da questão que deseja adicionar a sua prova, ou arraste a questão para o organizador de prova.

3

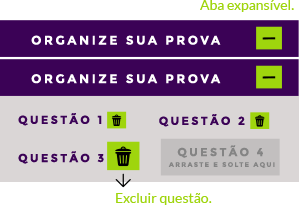

Use a aba do organizador para excluir ou adicionar as questões de nosso banco para a sua prova.

4

Quando estiver satisfeito com montagem realizada, clique em “Prévia da prova” para visualizar sua prova completa.

5

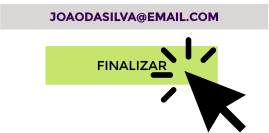

Se quiser retornar para editar algo clique em “Editar prova”. Caso esteja satisfeito, insira seu nome e e-mail nos campos e clique em “ Finalizar”.

6

Basta acessar os links da prova e gabarito que serão exibidos!